Balázs Szigeti

- Using tiny amounts psychedelic drugs to try to boost creativity and focus has become more popular in recent years.

- Iterable CEO Justin Zhu was fired last month for microdosing LSD before a company meeting in 2019.

- Experts told Insider the available evidence suggests the risks likely outweigh the benefits.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

The firing last month of Justin Zhu from the top job at marketing startup Iterable thrust the issue of workplace drug-use back into the conversation, highlighting an ongoing tension between individual performance-hacking and traditional corporate norms.

According to Zhu, the reason the board cut him loose from the company he co-founded was because he took a "microdose" of the psychedelic drug LSD before a company meeting in 2019, in the hopes of improving his focus.

While Zhu was by no means the first – or the highest-profile – tech industry leader to experiment with psychoactive substances to boost their professional performance, the company said it had a policy barring drug use among employees.

"Like it or not, this is an illegal activity," said Matthew Johnson, a professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins and the associate director of the university's Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, which was the first research group in the country to receive regulatory approval to study psychedelics with healthy volunteers.

"Microdosing has become such a fad, and particularly talked about in the tech industry, but these are Schedule I drugs," he said, referring to the US Drug Enforcement Administration's classification of substances with high risk for abuse.

Read more: How Entrepreneurs Microdose on Psychedelics to Spur New Business Ideas

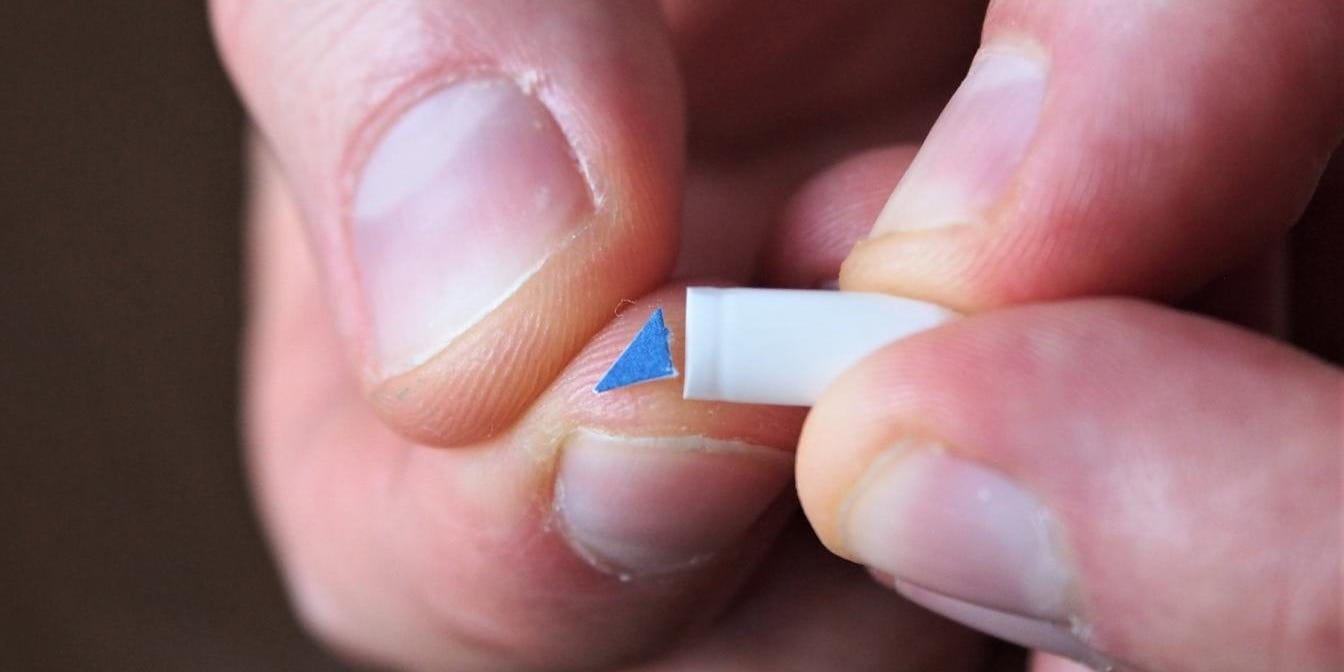

With microdosing, users take fractional doses of what might ordinarily be considered a recreational substance like LSD, ecstasy, or magic mushrooms, attempting to stay below the hallucinogenic effects the drugs are known for. In many cases, these low doses are repeated at regular intervals to achieve a cumulative effect over time.

As to whether it works, "my jury is still firmly out on that one," said Jamie Wheal, a researcher and writer on the neurophysiology of human performance, and the founder and executive director of the Flow Genome Project, which consults with high-growth startups and Fortune 500 companies like Google and Cisco.

"The biohacker bro is a relatively new version," he said. "I first noticed it probably a decade ago with some Google engineers and other places where some folks were beginning to see microdosing as a brain-hack optimization thing."

This ad-hoc experimentation is an extension of the academic research pioneered in the 1960's and 70's by psychologists like James Fadiman that was effectively shunted out of the mainstream in favor of the development of less potent alternatives.

"We could have had the Age of Aquarius - instead, we got Prozac nation," Wheal said.

Federally sanctioned research and commercial interest in therapeutic applications for psychedelics is generally focused on so-called "heroic" doses, and the results may give pause to anyone considering self-experimentation with microdosing.

Professor Johnson said he has heard from people who've attempted to measure out drugs on their own and been caught off-guard by the results.

"They intend to take a microdose, but then they're at work and the wall starts waving," he said.

Johnson said his research often compares heroic macrodoses of LSD or psilocybin with microdoses that effectively constitute a placebo or control group.

"If there is a benefit of microdosing, it's very likely that it has almost nothing to do with the types of effects that we're seeing with high doses," he said.

Steve Jobs, one of the most prominent psychedelic experimenters in Silicon Valley, said that "taking LSD was a profound experience."

"LSD shows you that there's another side to the coin, and you can't remember it when it wears off, but you know it. It reinforced my sense of what was important," Jobs said.

Indeed, research by Johnson and others has shown that heroic doses of psychedelics have been shown to have a host of benefits in clinical trials, but they also effectively incapacitate the user and require the close supervision of a trained professional to guide a person safely through the experience.

In other words, you wouldn't be able to lead a meeting - or do much of anything for that matter - when on the recreational or higher amounts of psychedelics required to experience the reported therapeutic benefits.

But the current findings indicate those benefits don't seem to transfer down the scale very well. Although some users claim to see attentional or creative benefits from microdosing, Johnson says the science just doesn't support the specific claims of heightened creativity and focus.

If anything, Johnson says "tinkering with the serotonin system" could have an ongoing benefit for mood, but that raises other medical concerns for cardiac health.

"If there is something there, I think the the antidepressant effects seem the most credible, and if it works, the most important," he said. "But psychedelics wouldn't be the on the top of my list to investigate to enhance focus."

Indeed, a recent study published in the journal eLife found that microdosing's reported benefits were largely attributable to the placebo effect. Considering the health, legal, and professional risks of a wrong dose, Johnson suggested revisiting a more familiar cognitive boost: caffeine.

"If you're not taking it every day, 200 milligrams of caffeine has some real performance and cognitive enhancing effects," he said.

Every company has its own culture and norms, but Johnson said he would see no contradiction if one of the several psychedelic startups looking to cash in on developing an FDA-approved therapy were to prohibit the sort of self-experimentation that got Zhu into trouble with Iterable's board.

"We've got safeguards in our research, and anything that sends to the FDA pathway, they're going to have safeguard the safeguards in place," he said.

When it comes to psychedelics, contrary to the Silicon Valley ethos of "move fast and break things," experts say it's better to go slow and follow the rules.